Important Information!

If you actually take IGCSE comp sci, ignore everything I say, because the examiners love seeing overcommented code for whatever reason, and they will even give you subjective marks based on if they think there are enough comments or not.

To them, “well commented code” is of higher quality, despite if 80% of the code is just paragraphs and paragraphs talking about the meaning of life.

Yes, I do have beef with these people. Write better code, comments are not an excuse to write bad code!

The Problem

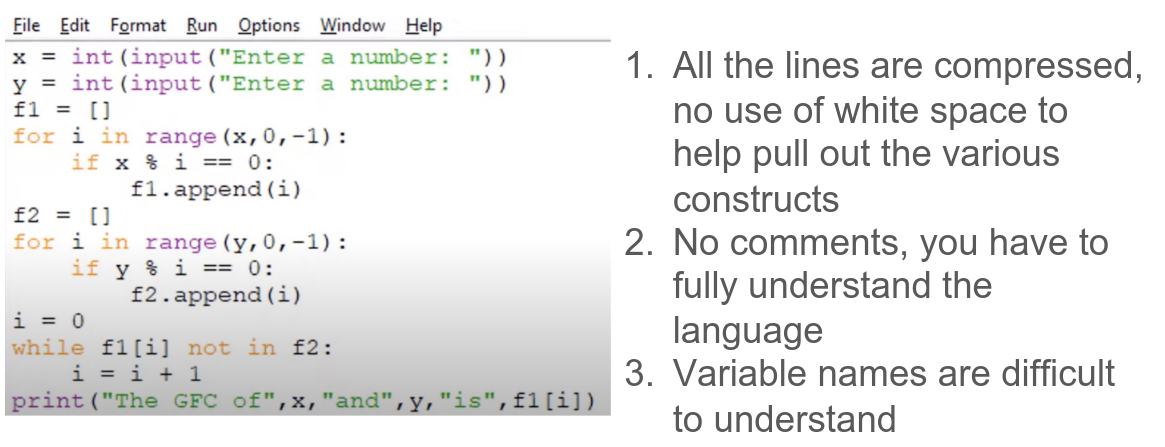

People are overcommenting their code nowadays; we are even taught to do this due to the stupid IGCSE Examiners giving marks for “good” commenting practices 1. Here’s an example from our computer science teacher:

To me, this looks like a completely fine set of code. I was asked by my teacher (because I think he knows that I’m quite the Good Programmer and he wanted my input). I said that:

The code looks completely fine to me, its good enough, readable, all I would do is run the code through a formatter and rename the variables.

Instead, I was told that I was Wrong for saying that, and that this was a badly written program. The biggest problem that was highlighted to me was that there were no comments, and therefore the program was unmaintainable.

(Written by my Comp Sci teacher)

I do agree that that having better variable names is objectively better, but this is clearly an example of overcommenting.

Why not comment?

Consider this code:

# grab the response after the message is sent

r = send_message(m)

# check if the message sent correctly

if r.status() == 9:

# mark as sent

m.sent = True

Adapted from CodeAesthetic’s Video

All these variable names, m, r, and the random 9 floating around isn’t very legible to anyone else who may be maintaining your code.

This is why there are many comments explaining what my code does. Future maintainers of my code would ideally read those comments and understand what the code is doing.

But do we really need all this many comments? If your code is unreadable and you need comments to fix it, why not just adapt the code?

We could easily rewrite this section like so:

# ...somewhere at the top of the file

MESSAGE_SENT = 9

# ...later

response = send_message(msg)

if response.status() == MESSAGE_SENT:

message.sent = True

Now the code reads itself. Everything is clear, and the code is self commenting; it reads like natural human language.

Here’s another example:

def get_time_from_server(server):

response = request_for_time(server)

if response.status == 1:

return -1

else:

return response.result

Now what happens if you didn’t have access to the contents of this function (if this were in a library); how would you know what the format of “server” should be, is it a list of values for an IPv4 address, is it an URL or URI, is it a string or a custom class? And how do you know what the return values mean?

Here’s the naïve solution implemented with some ✨comments✨

# grabs the time from a server.

# the server argument takes in a tuple with 4 integers,

# representing an IPv4 address.

def get_time_from_server(server):

response = request_for_time(server)

# If the value is 1, return -1 to mean an error

if response.status == 1:

return -1

# return the actual result

else:

return response.result

Unclean, right? Here’s some issues:

- Now what happens if the server actually sends -1 as some useful value, like representing a server-side error; would the caller of the function even know?

- What happens if we want to support IPv6? The parameter type would completely change, but if we forget to update the comment in a rush, that wouldn’t be very nice for the caller, right?

- We are, again, rewriting the code itself in English, which provides no extra worth to the reader.2

Here’s how I would fix it:

IPv4Address = tuple[int, int, int, int]

def get_time_from_server(server: IPv4Address) -> int | None:

response = request_for_time(server)

if response.status == 1:

return None

else:

return response.result

Now the function is a lot clearer, even without comments. Here, we use types to make it clear to the caller what data is supposed to come in and out, without ever needing to consult documentation (although that’s a bad idea!)

The only other thing that I would do in this case would be to annotate what None represents, i.e.

IPv4Address = tuple[int, int, int, int]

# returns None if there's an error

def get_time_from_server(server: IPv4Address) -> int | None:

response = request_for_time(server)

if response.status == 1:

return None

else:

return response.result

but again, we could just make a type alias.

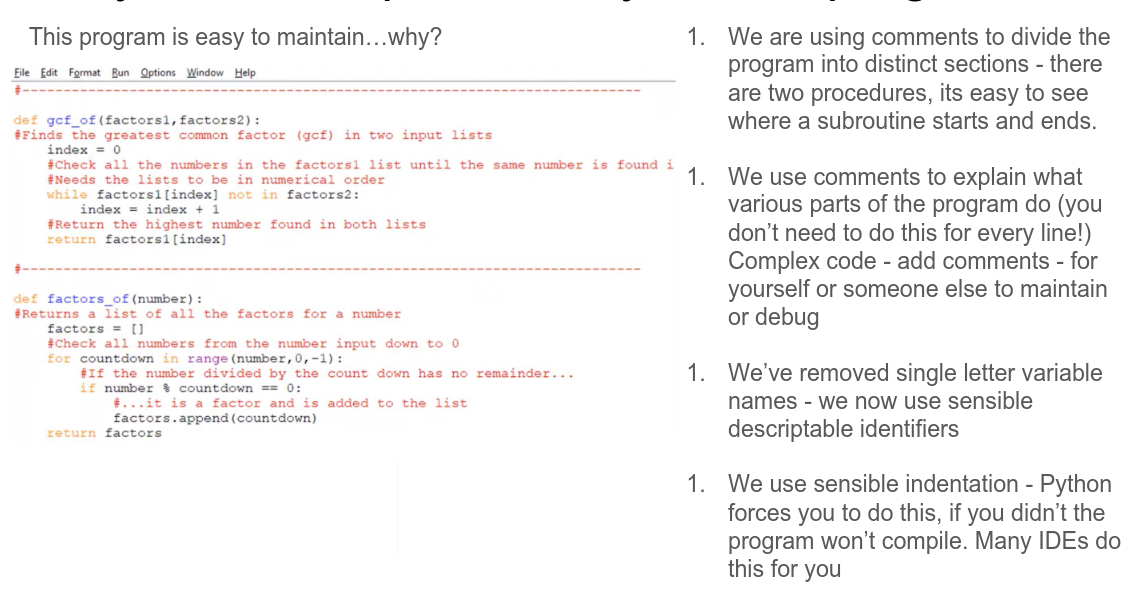

Example Refactor

Looking at the above example from my Computer Science Teacher, here’s the before:

x = int(input("Enter a number: "))

y = int(input("Enter a number: "))

f1 = []

for i in range(x, 0, -1):

if x % i == 0:

f1.append(i)

f2 = []

for i in range(y, 0, -1):

if y % i == 0:

f2.append(y)

i = 0

while f1[i] not in f2:

i += 1

print("The GCF of", x, "and", y, "is", f1[i])

Messy, right?

You could tell which part of the program does that, though:

- the first portion of the code that deals with f1 gets all the factors of x.

- the second portion of the code that deals with f2 gets all the factors of y

- the last portion of the code checks each factor of f1 and sees if it’s also a factor of f2.

- Since the list is in reverse order, i.e. largest factor goes first, the first common factor it finds should be the greatest.

But this is quite hard to decipher for a person that doesn’t know the algorithm; let’s refactor it.

x = int(input("Enter a number: "))

y = int(input("Enter a number: "))

x_factors = []

for possible_factor in range(x, 0, -1):

if x % possible_factor == 0:

x_factors.append(i)

y_factors = []

for possible_factor in range(y, 0, -1):

if y % possible_factor == 0:

y_factors.append(y)

index = 0

while x_factors[i] not in y_factors:

index += 1

print("The GCF of", x, "and", y, "is", x_factors[index])

The identifier names make it a bit easier to understand. Now the reader of the code can understand that the first part is at least related to finding the factors of a number.

However, we can do better; since these are all repeatable and generic sections of code, we might as well extrapolate them into functions and use an f-string:

x = int(input("Enter a number: "))

y = int(input("Enter a number: "))

def get_factors(num: int) -> list[int]:

result = []

for possible_factor in range(num, 0, -1):

result.append(possible_factor)

return result

def get_gcf(num1: int, num2: int) -> int:

factors_num1 = get_factors(num1)

factors_num2 = get_factors(num2)

index = 0

while factors_num1[index] not in factors_num2:

index += 1

result = factors_num1[index]

return result

gcf = get_gcf(x, y)

print(f"the GCF of {x} and {y} is {GCF}")

Now what makes this code so much better than before?

- Types: It is so much easier to track the flow of data simply by noting down the types. It is also easier to run type-specific operations on parameters as you know for sure what the type is and don’t need to backtrack.

- Good identifier names: Now the code reads like human language! There are no weird array indexes, all lines have some sort of human-legible meaning to them.

- No redundant comments: There are no comments, as the code simply reads like English, given that you know how Python Syntax works.

Notice how there’s no need for comments to explain what the code does?

- Now, let’s say if we changed the algorithm in the future. If we had used comments, they may slowly become outdated and not reflect what the code says.

- If we write our code in more human-friendly form with nicer identifiers, the code immediately gets clearer, just by reading function names.

When should I comment?

In the previous example, I (or my teacher) uses a set algorithm to get the greatest common factor, some widely-known set algorithm that doesn’t need to be changed. If we were trying to teach how that algorithm worked; this would be a sub-optimal example:

# Grab the greatest common factor between 2 integers

def get_gcf(num1: int, num2: int) -> int:

# Get the factors of both numbers

factors_num1 = get_factors(num1)

factors_num2 = get_factors(num2)

# Define an index

index = 0

# Keep iterating through the first list while there a given

# factor is not in the other list

while factors_num1[index] not in factors_num2:

index += 1

# when we find the common factor, return it to the call

# site

result = factors_num1[index]

return result

We are annotating as to what the code does. That’s bad; as programmers we know the syntax of the language we program in, why is there a need to rewrite the syntax?

This still doesn’t help your understanding of the algorithm; one could ask:

Why are we iterating through one list and checking it with the other; wouldn’t the condition be met on the first iteration because both lists are in ascending order?

And other such questions. A better way to comment your code could be:

def get_gcf(num1: int, num2: int) -> int:

# both lists are in descending order

factors_num1 = get_factors(num1)

factors_num2 = get_factors(num2)

index = 0

# the lists are in reverse, biggest goes first, so the

# first hit would be the greatest common factor.

while factors_num1[index] not in factors_num2:

index += 1

result = factor_num1[index]

return result

Instead, we use comments here to provide missing information that is not immediately clear; it says why the code is written in a certain way.

The takeaway

Commenting is bad; there is always some way to make your code cleaner and more organized without comments. The only times where you should comment is to say why the code is there, not what it does. Commenting is not an excuse to write bad code, write good code that reads itself later on.

Comments can lie, any compiler/interpreter or even linter will not statically analyze your comments to see if they match your code. However, code doesn’t lie, because it has to follow rules. There is no use for commenting if there is a tool that can tell if your code is correct or not.

One of the many reasons as to why I have beef with the examiners. ↩︎

Before you bring up how beginner programmers who are not good at programming will not be able to read this, that is their problem. Code is meant to be read by programmers, they should learn how to code well before they try to decipher other people’s code as in trying to work with them. ↩︎